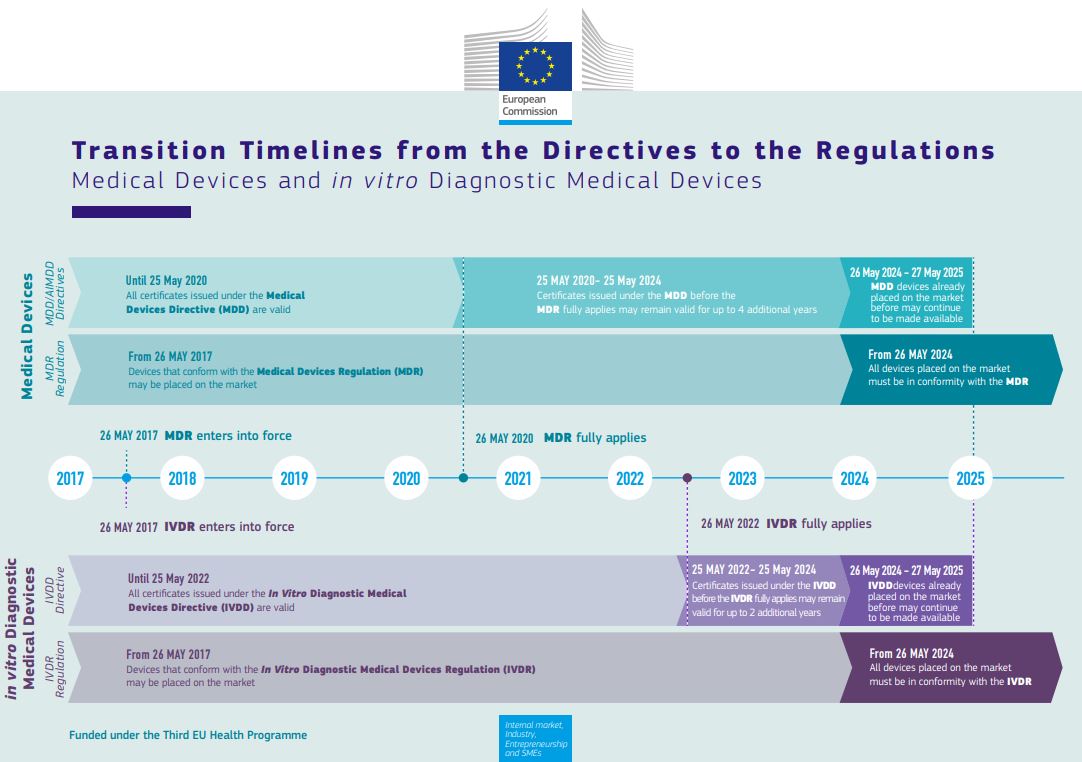

Set to apply from May 2022 on, the IVDR proposed progressive roll-out has been adopted by the EU as a very welcome Christmas gift.

Essential to realize thought is that the amendment does not change the requirements of the IVDR but only extends the implementation for certain devices. New devices or CE-marked devices not requiring NB involvement must still meet the 26-May-2022 deadline, and the requirements on the performance evaluation still stand, so the IVDR rollercoaster will soon take off!

So what is the challenge?

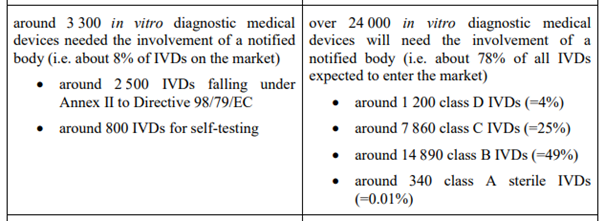

Referencing the amendment, we are moving from a situation where about 3300 IVD’s require NB involvement for their conformity assessment to a situation with over 24 000 requiring so. This while at the same time the number of NBs went down substantially, so there is a substantial shortage in resources in this respect.

But is that the only issue? Based on several conversations lately, and looking at this from a clinical perspective, we are facing another one, and that concerns the

performance evaluation,

or rather the lack thereof. The performance evaluation is meant to show that any (clinical) performance claim is subtantiated by sufficient qualitative evidence, and that the device performs as intended. Given the upclassification of so many devices, however, multiple manufacturers are new to or relative unfamiliar with this process, and I cannot but emphasize enough that they shall

“… plan, conduct and document a performance evaluation”

per Article 56 and Annex XIII of the IVDR, and that NBs will review

“… manufacturers’ technical documentation, in particular the performance evaluation documentation”

So a performance evaluation plan should be created, that includes key aspects such as

- the device with its performance claims (accuracy!)

- the target patient group(s)

- a justification as to why certain analytical, clinical, or other performance requirements are not considered applicable, or when required,

- the data that shall be generated in (clinical) performance studies, and

- the PMPF plan.

Especially on the last 2 bullets there appears to be some confusion, but let me help you out of your dream: a performance evaluation is NOT the same as a (clinical)

performance study

(or investigation, or trial). Studies are a way to generate the data needed for the evaluation, and in case of IVD’s we have

- the analytical performance studies that typically shall always be performed to generate data on the device’s analytical performance, and

- the clinical performance studies that shall be performed, unless due justification is provided, to generate data regarding performance in clinical practice.

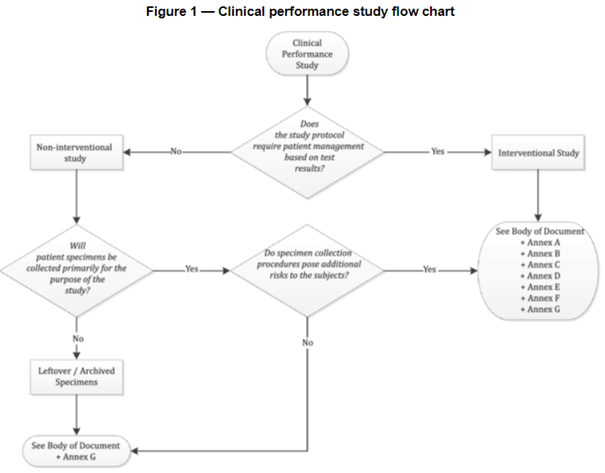

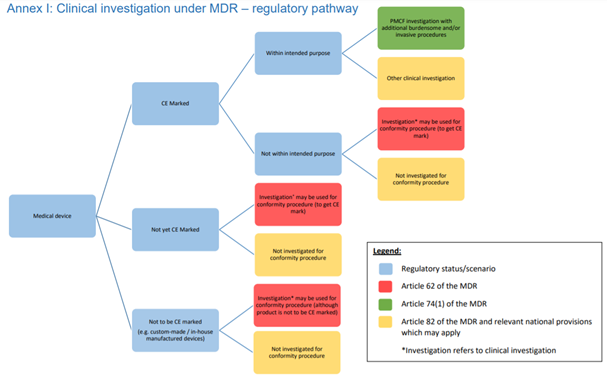

When necessary to substantiate device performance (even more so under the IVDR), such studies need to be conducted in line with international ethical and regulatory guidance, such as the Declaration of Helsinki, ISO 14155 (GCP for medical device on human subjects, and be aware that the IVDR references an outdated version!), and ISO 20916 (see flow chart).

Unfortunately at this stage the amount of

EU guidance documents

on the performance evaluation under the IVDR is limited in spite of the nearing deadline. As a starting point, however, and in line with the IVDR

“… guidance developed for in vitro diagnostic medical devices at international level, in particular in the context of the Global Harmonization Task Force and its follow-up initiative, the International Medical Devices Regulators Forum, should be taken into account …”

we do have IMDRF guidance (pretty old thought!) and the COVID-19 TEST MDCG that was published last year. So besides Annex XIII, there are tools on the performance evaluation process, and indicating what steps should be taken and documented. With respect to

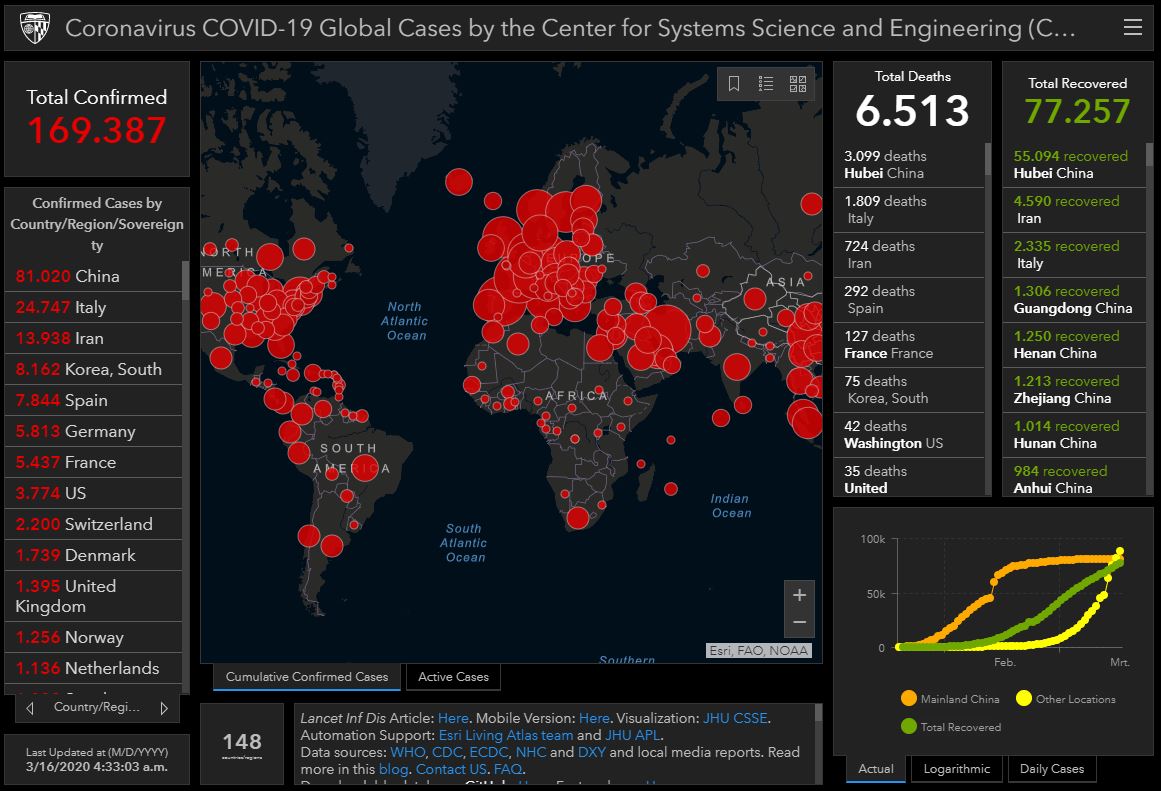

COVID-19 diagnostic devices

and press release on the adoption of the IVDR amendment, I found Stella Kyriakides’ comment that

“The pandemic has at the same time highlighted the vital need for accurate diagnostics and a resilient regulatory framework for in vitro medical devices. The amendment of the In Vitro Diagnostic Medical Devices Regulation will ensure that crucial medical devices, such as COVID or HIV tests, continue to be available and safe”

quite interesting: While, indeed, the pandemic emphasized the need for a smooth functioning regulatory system, to me it also illustrates – again – some of its shortcomings. Referencing Ines’ recent blogpost on this topic, COVID test devices have substantial flaws for multiple reasons, but in light of the performance evaluation I find it frustrating that one of the reasons is that devices have been benchmarked with symptomatic people rather than a-symptomatic ones (wrong target patient group!). This while at the moment they are often used by a-symptomatic people.

In short,

there is a lot of clinical work ahead of us ensuring performance evaluations for the IVD’s are in order and substantiated by adequate and qualitative clinical evidence. If not started to date, you better start preparing yourself right now, because the deadline is closer and performance studies take longer than you think, while the rollercoaster is about to take off.

Feel free reaching out in case of questions or support needed, and in the meantime I wish you a good and above all healthy New Year!

Annet

As updated 05-JAN-2022

I am very happy that as of April, we have more time until the date of application of the Medical Device Regulation, as well as more clinical guidance to work with. In my previous post I addressed my observations on the guidance for the

I am very happy that as of April, we have more time until the date of application of the Medical Device Regulation, as well as more clinical guidance to work with. In my previous post I addressed my observations on the guidance for the  Also conform MEDDEV 2.7/1 Rev 4,

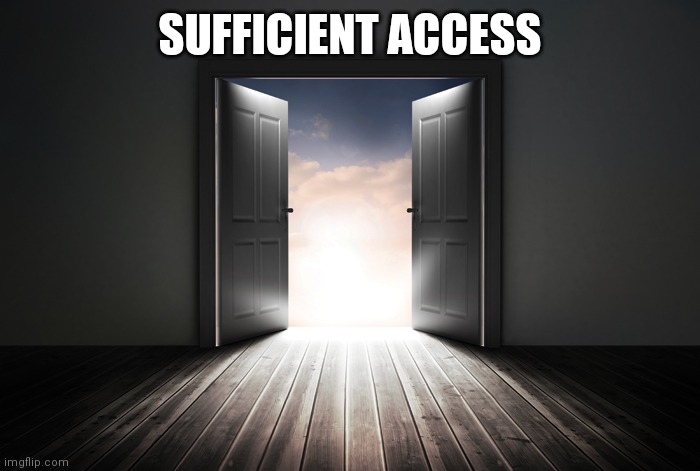

Also conform MEDDEV 2.7/1 Rev 4,  Another topic that received much attention since publication of MEDDEV 2.7/1 Rev 4 concerns the need for access to the technical documentation of assumed equivalent devices. Also here the MDCG 2020-5 guidance leaves no room for debate, and once more underlines that under the MDR a manufacturer must be able to demonstrate sufficient level of access to the data of the equivalent device, and that for Class III and implantables this means a contract must be in place with the manufacturer of the equivalent device allowing for ongoing access to the technical documentation.

Another topic that received much attention since publication of MEDDEV 2.7/1 Rev 4 concerns the need for access to the technical documentation of assumed equivalent devices. Also here the MDCG 2020-5 guidance leaves no room for debate, and once more underlines that under the MDR a manufacturer must be able to demonstrate sufficient level of access to the data of the equivalent device, and that for Class III and implantables this means a contract must be in place with the manufacturer of the equivalent device allowing for ongoing access to the technical documentation. After a long period of waiting, several delays, and the MDR deadline without proper guidance hanging above our heads like the Sword of Damocles, as of end of April we have

After a long period of waiting, several delays, and the MDR deadline without proper guidance hanging above our heads like the Sword of Damocles, as of end of April we have  MDCG 2020-1 nicely (re-)visualizes the general evaluation PROCESS, which is the same regardless whether we are dealing with medical devices, in vitro diagnostics devices, or MDSW, and describes the 6 stages we are (supposedly) familiar with: planning/ scoping, data identification, data appraisal, data analysis within the context of the Essential Safety and Performance Requirements, reporting, and updating throughout the product life cycle.

MDCG 2020-1 nicely (re-)visualizes the general evaluation PROCESS, which is the same regardless whether we are dealing with medical devices, in vitro diagnostics devices, or MDSW, and describes the 6 stages we are (supposedly) familiar with: planning/ scoping, data identification, data appraisal, data analysis within the context of the Essential Safety and Performance Requirements, reporting, and updating throughout the product life cycle. To date numerous guidances, blogposts, webinars have been published addressing what one must and cannot do in the process of clinical evidence collection due to the COVID-19 pandemic (for overviews see

To date numerous guidances, blogposts, webinars have been published addressing what one must and cannot do in the process of clinical evidence collection due to the COVID-19 pandemic (for overviews see  challenge, or quoting Erik “another crisis in the making”), and as (hopefully) known, an important activity concerns

challenge, or quoting Erik “another crisis in the making”), and as (hopefully) known, an important activity concerns  Provided there is study personnel available, however, participant visits can be

Provided there is study personnel available, however, participant visits can be  site data review is finished, you could consider performing the close-out by phone.

site data review is finished, you could consider performing the close-out by phone.

appearing in a hard to keep up pace, indicating what is the best approach with respect to

appearing in a hard to keep up pace, indicating what is the best approach with respect to  For proper SDV the CRA needs to be able to review the patient files. That tends to create challenges due to the fact that most of the hospitals in Europe do not allow for remote (so off-site) viewing of patient files by the sponsor due to (possible)

For proper SDV the CRA needs to be able to review the patient files. That tends to create challenges due to the fact that most of the hospitals in Europe do not allow for remote (so off-site) viewing of patient files by the sponsor due to (possible)  othing could have been more illustrative for the medical device clinical trial environment in Europe than the storms Ciara and Dennis in February. With BREXIT as a kick off, the Coronavirus spreading around te globe, the MDR deadline less than 3 months away, and a new version of ISO 14155 coming out shortly, 2020 for sure guarantees a stormy year for any-one involved in medical device clinical trials

othing could have been more illustrative for the medical device clinical trial environment in Europe than the storms Ciara and Dennis in February. With BREXIT as a kick off, the Coronavirus spreading around te globe, the MDR deadline less than 3 months away, and a new version of ISO 14155 coming out shortly, 2020 for sure guarantees a stormy year for any-one involved in medical device clinical trials In the meantime, let’s not forget the MDR DEADLINE being right around the corner. With a substantially higher demand for qualitative clinical evidence, and, as a brief reminder, reasons for this include that:

In the meantime, let’s not forget the MDR DEADLINE being right around the corner. With a substantially higher demand for qualitative clinical evidence, and, as a brief reminder, reasons for this include that:

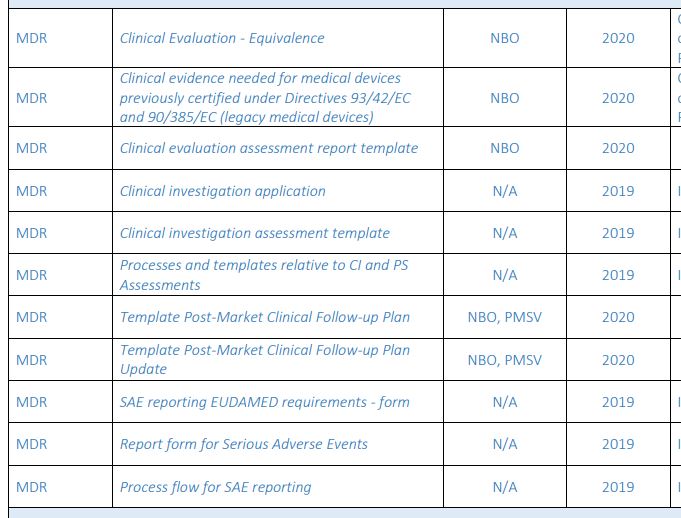

Guidance documents issued sofar with interesting clinical aspects include the following:

Guidance documents issued sofar with interesting clinical aspects include the following: In conclusion, with the MDR deadline around the corner for all the applicable devices (all new medical devices, not upgraded class I devices, and class IIa, IIb, and III devices with significant changes) for clinical activities & documents, we still need to rely on our own interpretation of the applicable sections in the MDR in combination with existing guidance documents for the MDD and the AIMDD. Let’s keep out fingers crossed that for patient’s safety sake, all parties involved have a similar interpretation while working on the collection & evaluation of clinical evidence substantiating safety and performance of the concerning medical devices.

In conclusion, with the MDR deadline around the corner for all the applicable devices (all new medical devices, not upgraded class I devices, and class IIa, IIb, and III devices with significant changes) for clinical activities & documents, we still need to rely on our own interpretation of the applicable sections in the MDR in combination with existing guidance documents for the MDD and the AIMDD. Let’s keep out fingers crossed that for patient’s safety sake, all parties involved have a similar interpretation while working on the collection & evaluation of clinical evidence substantiating safety and performance of the concerning medical devices.